How To Clear Bobcat Fault Codes

She has endured gossip as the most famous jilted spouse in Silicon Valley and been idolized as America's most daring CEO, but the proper title for Anne Wojcicki is DNA safecracker. She's opening the vault that keeps information about you from you, starting with your genetic code. Sure, the 41-year-old first landed in the headlines as Google co-founder Sergey Brin's other half, but it's as the co-founder of the genetic testing company 23andMe that Wojcicki (pronounced Woe-JIT-ski) has become a harbinger of the future of healthcare.

When 23andMe launched in 2006, with hefty backing from Google, its mission was clear: Give individuals direct access to their genetic makeup and explain what that information may predict about their future health so they can make proactive choices about their care. Competitors came and went; 23andMe seemed destined to dominate a field it had practically invented. But then the FDA shut down most of the operation in late 2013, in part because the agency believes potentially frightening test results should be disclosed only under doctor supervision, not directly to a consumer.

"I've never shied away from the fact that we generate information that may be life-changing," Wojcicki says. "You might find out that your father is not your father, and you have a sibling that you don't know about. And if I can tell you that you are also at higher risk for melanoma, that might send you to get your skin checked." She is adamant that patients are smarter than they're given credit for being, and she believes that "people can crowd-source solutions" for themselves. Before 23andMe was curtailed, the company's test, called the Personal Genome Service, was available for only $99. The pitch was simple: You send in spit; you get an e-mail that contains a link to detailed information about your genes: what you inherited from your parents, what your ancestry might be, what diseases you might be at risk for. Now you can still get ancestry analysis and raw genetic data, minus the health indicators. (Citizens of Canada and the U.K. recently gained access to the original test for about $200.)

The medical establishment has yet to come around to 23andMe's DIY approach to wellness. Wojcicki laughs as she relays a conversation she had with a dermatologist, who said (bro to bro, apparently), "Dude, stop sending people to get their skin checked. Do you know how much I get paid for that? Do you know how much more money I make when I do Botox?" It's exchanges like this that convince Wojcicki that the current healthcare model needs to change, even if physicians might remain outside the equation.

Even though I'm a doctor, I'll admit there are times when it doesn't make sense to put us in the middle, where we are often no more than rushed messengers. Especially not these days, when it's possible for a patient to already be armed with quite a lot of information about themselves, thanks to wearable technology that can track activity, sleep, and calorie intake.

Wojcicki, who freely calls herself dude as well, is speaking to me in a conference room in 23andMe's one-story office building in Mountain View, California, literally in the shadow of Google's headquarters. In true Silicon Valley style, one quarter of the floor is left open for company CrossFit classes, half of the workstations are standing desks, and there are few actual offices, even for the CEO. Wojcicki has just finished Facetiming with her six-year-old son, who is on his way back from camp. (She also has a three-year-old daughter.) During our conversation, texts from Brin interrupt us several times. Though the couple are not divorced, they now live apart—and have since the Google co-founder became romantically entangled with a 27-year-old employee. Wojcicki says that they're active co-parents in the midst of what appears to be a pretty amicable breakup.

The seeds for 23andMe were planted when Wojcicki worked at an investment fund on Wall Street. She jokingly says she left New York to return to the Bay Area, where she grew up, because she couldn't face one more meeting in a strip club. But in truth she had been evaluating and investing in healthcare and biotech companies and figured it was time to turn the whole thing on its head. "I was really frustrated with how consumers were treated in healthcare," she says. "They don't really get that much choice." Her goal, she says, has always been to give it back to them.

To do that she and co-founder Linda Avey decided to help people unlock their own genetic codes. Each of us has about 20,000 genes that make up our individual DNA. Those genes are arrayed in each of our cells into 46 separate strands called chromosomes, which are organized into 23 pairs—the 23 of the company's name—each of which contains a chromosome from each of our biological parents. When it's our turn we pass on one chromosome from each pair to our offspring. Most of these genes are like distant stars in the galaxy: We don't know much about them, but we are slowly finding out. We now know, for example, that a mutation (which Angelina Jolie carries) in the BRCA gene indicates an increased risk of both breast and ovarian cancer. Other mutations can lead to an increased likelihood of getting the fatal neurological condition called Huntington's disease, or of manageable health issues like high blood pressure.

There is a long list of genes we think are correlated to serious diseases, but we don't understand how or why. Many may be caused by multiple genes working together; some combinations make you sick, and some don't.

To help interpret the range of genetic differences the company was finding in its customers, 23andMe eventually started relying on something called genome-wide association studies, which search for patterns across a person's entire genetic makeup rather than looking at one gene at a time. But with the scarcity of data available to us today, it's a little like trying to figure out if someone has a good poker hand when only a couple of her cards are showing. It's a lot of educated guesswork.

That was another objection from the FDA, which considered some of the connections that 23andMe provided overconfident, and potentially wrong. In its letter to the company telling it to stop selling its genetic interpretations to customers, the agency said that "serious concerns are raised if test results are not adequately understood by patients or if incorrect test results are reported." A spokesman for the FDA told me that there are also "no guidelines for healthcare professionals on how to use these test results."

Wojcicki agrees that there is still much to learn. And then she says something that shows that her DNA is all Silicon Valley: what we don't know today data will answer tomorrow. She imagines the day we learn about genes and their effects the same way Google learns from people searching the web. Google's searches get smarter by generating data and observing how searchers respond. If Wojcicki could gather the genetic and health information of, say, a few million people, she could find the same kinds of connections. After all, the way researchers recently discovered a gene found mostly in Latina women that protects against breast cancer was by analyzing data from about 11,000 women.

Spencer Lowell/Trunk Archive

For now, amid all the red tape, Wojcicki is trying to wedge the door back open with the FDA. Though I'm the one who went to med school, she knows far more about genetics than I do. My training in the subject (which was fairly standard) consisted of a few lectures I half slept through in the early 1990s, a decade before the first human genome was fully sequenced. So it's sort of a paradox that the FDA trusts my kind, and not hers, to communicate genetic information.

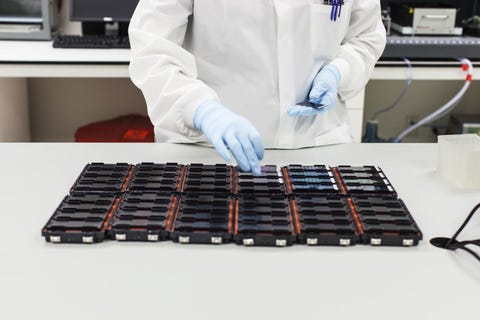

Wojcicki is now trying to get approval to give test results and the accompanying interpretation for one genetic defect in particular. It's called Bloom syndrome, a rare condition that causes short stature and a greatly increased risk of cancer. At the moment she has 800,000 DNA samples in her database. To find more genetic connections with any certainty, she'll need several million.

The value of these samples was proved at the beginning of this year, when the biotech giant Genentech agreed to pay up to $60million to Wojcicki's company for access to samples from patients with Parkinson's disease and their first-degree relatives.

While 23andMe was reined in by one government agency, another, the famously choosy National Institutes of Health, just gave it a $1.4million grant to turbocharge the company's web-based capture of data from patients, so that some day it can marry what the company finds in your DNA with what you tell it about your health.

Even though she's now colossally wealthy—something that seems hard to reconcile with the woman in the moisture-wicking workout shirt laughing and juggling a dinged-up iPhone with a dead battery—Wojcicki often refers to work she did in her twenties, when she was a volunteer patient advocate at Bellevue Hospital in New York and later at San Francisco General. She asks me to speak for my profession and explain why patients still can't see their own results from clinical research studies they join. The best answer I can provide is that it has always been this way. "People should be able to decide where their data goes," she says. "If you want to share it for breast cancer research, then you should be able to decide to do that." This is just one of the many popular conventions in healthcare she is determined to challenge.

Wojcicki may be controversial, but she has earned the respect of even her competitors. Randy Scott is a co-founder of Invitae, a genetic testing company that works directly with doctors and genetic counselors, not customers. About Wojcicki he is clear: "She's a sincere advocate for patients and is bringing the whole field along by challenging old ideas about what consumers should be told and what should be kept from them." If Wojcicki has her way, consumers will be told everything and shielded from nothing.

For doctors, this might mean patients come to us with a lot more questions, and I may have to look over a lot more of my old lecture notes. But odds are they will be coming to me with a lot of answers, too.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io

How To Clear Bobcat Fault Codes

Source: https://www.townandcountrymag.com/style/beauty-products/news/a2773/meet-the-woman-who-wants-your-dna/

Posted by: arguetamonatur.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How To Clear Bobcat Fault Codes"

Post a Comment